Is it the drum or the drummer, the carpenter or the hammer? You know the old debate. It’s like asking whether it’s the ballplayer or the bat. There are two sides to this discussion, with no definitive right or wrong in my opinion.

From my experiences, I’ve seen incredible drummers produce amazing sounds on what many would consider “bad” drums. I have a talented friend who plays Brazilian-style hand percussion, and he can make a garbage can lid sound fantastic.

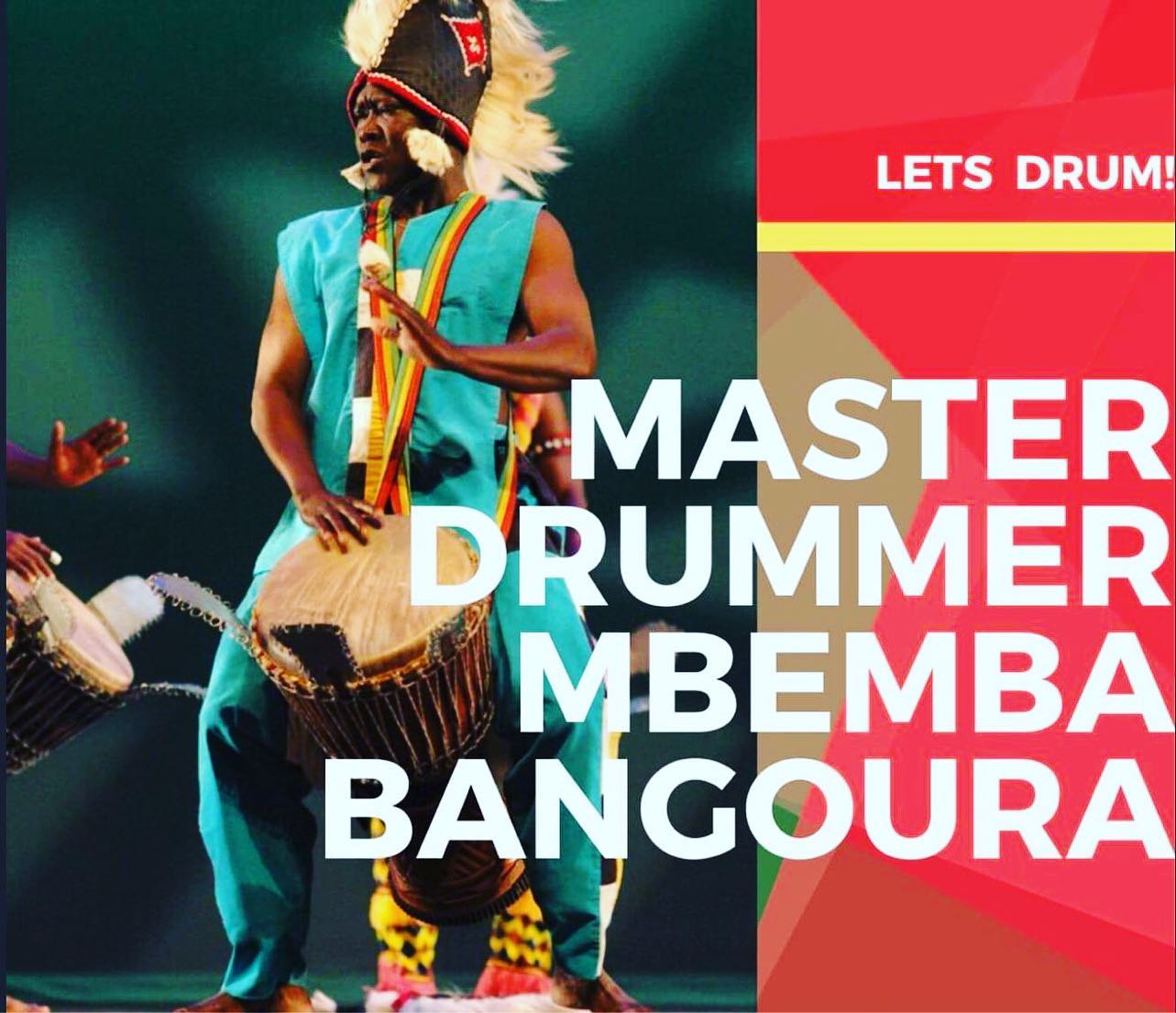

I had a drum that I was playing at an M’Bemba Bangoura workshop in Florida. I thought it did not sound good and was frustrated by it. During a jam at the end of his class M’Bemba came over and played it. It sounded amazing and I fell back in love with it. I have a video of this by the way if you want to see it. Obviously, I needed to work on my technique.

In Mali, I encountered drum sets being played in musical situations, even with famous bands, that could only be described as prehistoric. I’ve witnessed drummers performing with tree twigs for their drum set. They were nice tree twigs, but not even, balanced drum sticks like we are used to seeing or using.

When I brought them quality drumsticks from a music shop on my next trip to Mali, they appreciated the gesture but continued to use their tree branch sticks instead. People get accustomed to certain tools. And that’s another possible side to the equation.

My teachers in Mali, who were from the older generation, would play whatever drum was in front of them, where as the younger group of drummers there where I was studying, all coveted one special drum, a super nice calf skin roped djembe that was super cranked up, (tuned to a high pitch for solo).

Aruna and Brulde, me teachers, would tune the drum they were playing with a gnarly rock, something I never saw before in any other part of the world. It would give me the chills, but that’s how they do it!

So what’s the takeaway? While it’s true that master drummers can create wonderful sounds with any instrument, they don’t intentionally choose inferior drums. Unless that is all they have. Then they make do.

Every exceptional West African drummer and djembe teacher I know in the “new world” so to speak, possesses a beautifully crafted drum. In Cuba, they make do with what they have, but if you offer them a high-quality drum, they’ll embrace it with enthusiasm.

No one will ever say, “This drum is too beautiful; I’d rather play this inferior one.” That simply doesn’t happen. Everyone enjoys playing a great sounding, quality made instrument no matter what their level of playing ability. It is simply very helpful.

Think of it this way: if you were a carpenter, wouldn’t you prefer to use a lightweight power drill instead of turning screws by hand? You’d naturally opt for the better tool and the more efficient method.

That said, many of us (myself included) can get swept away by aesthetics, craftsmanship, and the art of music-making, sometimes overlooking the necessity of honing our technique to produce better sound—not just relying on a fine drum.

It truly is a balance between the two. In my personal journey, I find that a high-quality drum with a fantastic skin—whether it’s a conga or a djembe—provides me with inspiration and joy, encouraging me to play.

It helps me achieve “my sound.” We just need to remember that while the drum plays a role, it’s ultimately our technique that matters most in creating the music we desire. And, it’s super fun to do it on a really nice drum! to me it’s not as important how it looks as how it sounds. However, I have and love beautiful drums.