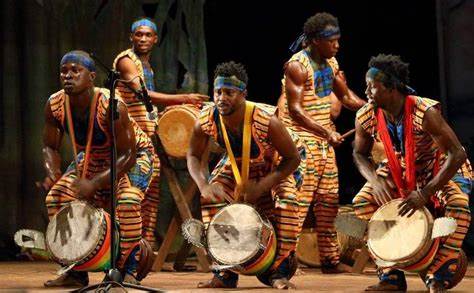

Embracing Traditional Folkloric Drumming: A Guide for Hand Drummers

As a new hand drummer diving into the world of traditional and folkloric music, you may be seeking guidance on how to play in an ensemble, jam with others, or even take a djembe solo. If that resonates with you, I’d like to share some valuable insights on accompanying the djembe within a traditional drumming context, as opposed to a more casual “mixed” jam or drum circle setting.

It starts with learning all about play the accompaniment djembe parts for any given piece.

First off, I want to clarify that my intention is not to say anything negative about drum circles. This is not about them one way or another. This is about playing traditional of folkloric, village style or ballet style drumming, We are going to explore the unique elements of traditional drumming that set it apart.

The Importance of Listening

One of the most critical components of playing with others is the ability to listen—truly listen. This means shifting the focus away from your individual needs and listening to other peoples parts. It’s a challenging step, especially if you’re coming from a drum circle background, where individual expression is first and foremost.. In traditional settings, however, you’ll want to have an open mind, adopt a clean slate and be prepared to learn anew.

Holding Accompaniment Parts

In traditional drumming styles, the role of the djembe player always involves holding steady accompaniment parts. These parts are typically consistent throughout a piece, only changing when called for by a specific arrangement, or if the leader wants you to change.

Think of it like being in a symphony; your rhythm locks in with the others, creating a layer of sound that has been proven effective over time across various folkloric traditions—from West African and Congolese to Haitian, Afro-Cuban, Trinidadian, and beyond. It’s a tried and true method. Who invented it? Who knows, but it works to create cohesive percussion pieces and compositions.

In West African drumming music and all other drum music coming from the diaspora such as Afro Cuban, etc., people play parts. People do not solo at the same time,. People take turns. There is no “collision” of parts. Even when the parts move, it is not chaotic, it is pinned and precise, a language with in a language so to speak.

Your primary focus is to learn these parts and hold them. They key is to make them work. To make them come alive and to really find the groove. That is the mystery and the task that many people miss, don’t learn or are unable to comprehend. That playing a simple part, perhaps only with 4 or 5 notes, can be so important and be incredibly funky and soulful!

Later on down the road, or on your own time, once these accomapniment parts are ingrained in your consciousness, you can begin to experiment and explore ways to creatively adapt or solo on the djembe coming out of these parts and returning to them in a call and response with yourself. But let’s not rush ahead just yet!

The Art of Accompaniment

While advanced players may engage in conversations through their drumming, traditional djembe accompaniment takes a different approach. The goal is to create a cohesive sound rather than simply showcasing your individual rhythm. When you solo you can do this but we don’t ever do this when we are playing “support” because this is what accompaniment it as well. We support each other, the rhythm, the dancer, the class, the situation.

Sometimes, for some people, this can be frustrating. Especially for those transitioning from a drum circle, where personal expression often dominates. Some may find the repetitive nature of accompaniment dull or akin to playing a “penalty part.” I like to use the example of a mantra for meditation. A mantra repeats and does not change. It helps to bring your consciousness higher. Drumming is no different. You can get the same exact benefits playing accompaniment as meditating. That’s my personal experience anyway!

What is interesting to me, as a side note, is how much resistance I get from people when I explain this correlation. Because people think, believe, are taught, yoga meditation is one thing, and they have come to believe drumming is another thing. So it does become about adjusting our belief systems sometimes.

In many Western cultures, we struggle with the concept of holding steady rhythm patterns. Our fast-paced society pushes us to be doers rather than listeners. We are motivated by the idea that more is better, confusing stagnant repetition with a lack of creativity. Most people have a very hard time believing that holding a part, playing support, being the groove is as creative as moving the part all around, starting and stopping and doing their own thing entirely.

However, creating a deep groove through solid accompaniment allows you to understand the nuances of rhythm, groove, pocket and timing. As you focus on your part, you’ll learn to identify where you fit within the ensemble, particularly in relation to the dunun drums. These elements are the precursors and necessary for being a great soloist.

Playing Accompaniment

So, how do you actually go about playing accompaniment? When you are in a group setting, the process begins with waiting for the lead drummer to call a signal, often referred to as “the break,” or call, before you enter the groove in sync with the other players.

Your volume should be loud enough for you to hear yourself, without overpowering the group. Accompaniment volume should be lower than the lead drum volume. Most people have a tendency to play louder when the lead drummer plays loud so you have to train your self not to do this. You only have to play loud enough to not to get lost in the mix, especially if you’re playing with less experienced drummers who might come in too strong due to enthusiasm or ego. However, the leader may ask for louder or stronger playing at times.

Keeping your concentration on the groove is key. If you find yourself playing in a dance class, observe the dancers’ movements; their feet and bodies will provide cues to connect your rhythm to theirs.

Relationship with the Dunun

In traditional West African ensembles, a vital element is the relationship with the dunun, a set of either one, two or three double-sided bass drums. Many refer to them as djun djun, but I prefer the Guinean name and term dunun.

My Guinean teachers say that calling the dunun, djun djun or djuns is incorrect, as it is the name of the Nigerian talking drum. However in some other cultures, and especially in drum circle culture, some call it djun djun. So there is a slight discrepancy around the name. I don’t want to bother getting into all of that, suffice to say different people use different names. And really it’s probably just the effect of different languages, no one is right or wrong, at least in my thinking.

These drums form the foundation of the group’s rhythm, melody and emphasize timing and grounding. Because there are bells on top (or played in the air with one hand called the “clutch” in Mali), there is a whole other layer of sound in a higher range that goes along with the dunun. So in a setting with 3 dunun, there are also three bells so we have a total of 6 different parts, in sex different ranges as the bees are all different pitches!

The dununba, the largest and lowest drum plays the bass and accents the composition, while the sangban plays the melody and rhythm. The kinkini, the highest drum, does not play a bass note, it functions as a metronome, maintaining its rhythm throughout the piece.

Many teachers, including myself emphasize learning the dunun parts before the djembe. Or at least at the same time. It’s the whole song. By playing each dunun part in an ensemble setting and hearing other peoples parts in the ensemble, you get a very different perspective of the piece. Sometimes you will find it sounds completely different each time you play a different part!

TraditionalIy, all players learn all th parts to any given piece. And I have never met a great drummer who cannot play dunun or who does not know the full composition of the piece they are soloing to. The whole concept of it is only about the solo djembe is incorrect. It is about the whole piece. Not only that, it is also about the dance and the song because usually there are many for each and eery piece no matter what drumming tradition we are talking about.

Please note that in West African style drumming, there is village style drumming that may have one, two, three or no dunun. The rhythms are played at different tempos than the city or ballet style which can often go blazingly fast and very many sudden changes in the piece.

Ensemble playing with a set of 3 dunun played sideways with a bell on top and on stands or the ground became popular with masters such as Famoudou Konate, Mamady Keita and Bolokada Conde, and is not as old a style as traditional or village style, but plays the rhythms from many different places such as Ivory Coast, Senegal, Mali,Guinea all with in the same 3 dunun format. Som people call this traditional but arguably, it is not.

Village-style drumming is often characterized by its roots in local communities. It plays a pivotal role in social gatherings, celebrations, and daily life.

Traditional drumming is often more communal and tied to rituals, celebrations, and storytelling within specific cultural contexts.

Ballet-style music is often associated with performance arts, particularly professional dance troupes that may be influenced by Western theatrical traditions. Ballet style was originally created by combining many different styles of drumming and dance from many different regions and areas and adding additional choreography theatrics, gymnastics and many other elements to make it exciting for a seated audience to enjoy,.

When you begin to explore soloing, pay attention to the dunun. While you could dominate the composition by blasting over the top of it and not even listening to the parts, which some people do, weaving in and out of their rhythms is far more musical and engaging.

Whether the dunun is played by one person using all three drums or by multiple drummers, syncing with them is essential for creating a unified sound. Dunun playing embodies the spirit of unity—it’s about crafting group sounds rather than individual expressions.

Preparing to Play Together

Again, to prepare for ensemble playing, a solid approach is to learn the dunun parts before joining others. Familiarizing yourself with their rhythms will enhance your interaction with the ensemble. If the full patterns seem daunting, focus on mastering the kinkini, the simpler, higher-pitched part.

To me, It’s all about taking baby steps or one step at a time. Because it also takes time to learn to hear everything as well. We are not accustomed to this music if we were not born into the culture or brought up listening to it and it is very different than western music or western drumming as well!

This foundational rhythm will anchor your playing and make integration into the group smoother.

Conclusion

So why go to all this work? “I just want to have fun” Ensemble playing, traditional, folkloric or village style drumming is deeply rewarding. When it locks up or locks in, when all the connections are made it is a magical experience. It is musical and inspiring and I would venture to say you can go much deeper with it than you can in a chaotic jam. Of course this is my experience and my belief system which obviously is different then others.

By embracing these principles, not only will you enhance your skills, but you will also enrich your experience of playing within an ensemble. Remember, traditional drumming is about connection, communication, and the beautiful creation of music together. This is just the beginning of your journey into accompaniment in traditional folkloric drumming. Stay tuned for more insights and tips on how to deepen your understanding and your participation in this vibrant musical realm!