The Drum Circle vs. Traditional Drumming: Let’s Set the Record Straight!

Are you a drum enthusiast, someone just dipping their toes into the world of drumming, or perhaps you’ve been pondering the differences between drum circles and traditional or village-style drumming? You’re far from alone!

Throughout my journey as a drummer, I’ve had the pleasure of engaging with musicians from both sides of this vibrant spectrum. Having participated in both drum circles and traditional drumming contexts, I can assert that there’s an overwhelming amount of passion, creativity, and conviction on both ends. However, there are also significant differences worth exploring. So, what really sets these two approaches apart?

For many involved in drum circles, traditional drummers might seem a bit uptight or rigid, appearing reluctant to embrace experimentation and spontaneity. Conversely, traditional drummers often perceive drum circles as chaotic, unmusical, and lacking structure, where participants play whatever they wish without a cohesive sense of rhythm or melody.

Drum circle enthusiasts frequently embrace the mantra of “there are no wrong notes,” advocating for the idea of self-expression and interpersonal connection through rhythm. They thrive on the idea that drumming is about feeling and interaction. To someone who studies traditional or folkloric drumming there are certainly wrong notes.

A local drum circle host I spoke with articulated the essence of this perspective beautifully: “It’s not about making music; it’s about having fun.” He relished moments when drummers’ beats would clash, finding joy in the clash, chaos and cacophony of sound that traditional drummers might avoid.

For him, the experience of drumming is about communal enjoyment over individual perfection. He also told me he can not hear the difference in between slap and tone, the two major components of making sounds on the conga drum and djembe drum. He also said he can not tell the difference between the sound of a professional drum and a tourist or cheap model.

I asked him about his hearing and he said it was fine. I don’t write this to criticize him, or make anyone feel or look bad, just to point out the difference in perception, understanding and levels of musicality we are dealing with.

And indeed, these ideas encapsulate the heart of many drum circles—creating a sense of community, embracing chaos, freedom and fostering camaraderie through what some may regard as hybrid, fusion, or free-form drumming. In such environments, anything goes!

Interestingly, individuals from highly educated backgrounds are often drawn to the drum circle scene. Yet, quite a few express a reluctance to delve into the historical or technical aspects of the instruments they are engaging with. Many of these participants proclaim, “I’ve spent a lifetime learning; now I want to express myself freely!” However, as we all know, life rarely offers free rides.

The notion that one can simply enjoy the art without the labor of learning is a misconception. Eventually, many encounter barriers—whether it’s hand strain from incorrect techniques or the tedium of playing the same rhythms repeatedly. Playing a musical instrument, much like learning guitar or piano, demands effort, understanding, and a commitment to mastering its nuances.

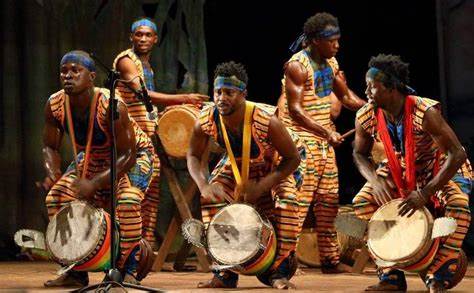

Now, let’s explore the realm of traditional drumming. Traditional drumming is made up of both village style drumming and what many people call “ballet style” or performance style drumming which uses elements and rhythms from the village but are sped up and changed somewhat, sometimes to make the pieces more exciting for a seated audience in the city. Both styles however utilize the same principles of holding parts, the use of compositions and are highly musical.

For those who engage deeply with traditional or folkloric styles, particularly from regions like West Africa, drumming transcends mere recreation; it’s a disciplined art form that necessitates commitment, practice, and robustness. Traditional West African music for example has hundreds of compositions, possibly thousands, that include different styes of drums, singing, dance and a purpose or meaning.

For example the Kassa rhythm family is to help the workers be inspired for harvest. There are baby naming ceremonies, weddings, full moon celebrations, coming of age ceremonies and on and on. Everyone is playing plays a part. An individual part that he or she holds. Like a repeating mantra. They do not change the part , they lock in and hold the parts. the parts interlock. The parts are all different.

In djembe music there are dunun, double sided bass drums . The kinkini, the highest plays a metronome part. The sangban, the middle drum plays a melody part, the dununba, the lowest “mother drum” if you will plays the bass part.

Conversations happen between the sangban and doununba that also relate to the dancer. It all works together to creat a folkloric system of call and response on several different levels.

The djembes do not ever solo at the same time like at a drum circle. The djembe players hold magical accompaniment parts and there is a soloist or they take turns. There is no chaos. It is a musical composition and arrangement.

Studying these styles involves not just learning individual parts, but also learning how to hear and listen to the music. It also helps you in developing an intricate understanding of the rhythms and compositions. Traditional drummers invest time in recognizing distinct patterns, appreciating the layered complexity of this musical heritage.

A striking challenge that participants in drum circles often face is the difficulty in perceiving the structured beauty of traditional rhythms. After immersing themselves in the loose, unrefined nature of drum circles—often characterized by a “wall of sound” or what my friend David likes to call “the drone sound”—they may struggle to discern the subtleties of traditional drumming. This experience can be likened to encountering a rich tapestry of sound only to be met with a flat, monochromatic canvas when expectations are misaligned.

Several years ago, during my study of Haitian music, my instructor gifted me a “top-secret” tape filled with intricate rhythms. At the time, to my inexperienced ears, it all melded into a wash of sound—indistinguishable and overwhelming. I placed the tape away, believing I was incapable of understanding its intricacies. Yet, after a year of dedicated practice, I stumbled upon the tape again.

This time, I was astounded; I could distinguish various tempos and specific parts. Each rhythm revealed itself as an individual piece of a greater mosaic. I couldn’t help but call my teacher with excitement, only to discover that indeed it was the same tape. This transformative experience underlines the vital truth: one must invest in understanding to truly appreciate the depth of music.

As some musicians transition from the informal vibe of drum circles to the structured world of traditional drumming, they often find the spontaneity of the former less appealing. Observing others who may not be attuned to listening or following rhythmic cues can shift their perspective and enjoyment.

You may find yourself asking: “What’s wrong with drum circles? Surely they are all about fun and inclusivity!” While this sentiment holds true, and drum circles can indeed ignite passion and collaboration, they often lack the depth and enrichment that comes with studying traditional styles, particularly for those wishing to elevate their skills.

There exists a broad spectrum within drum circles, from those guided by a facilitator who introduces various rhythms and practices to completely free-form gatherings where anyone can join in at any moment. For individuals genuinely eager to refine their craft, immersing oneself in traditional drumming can offer a treasure trove of knowledge and skill development.

So, is one approach right while the other is wrong? Not at all. Each methodology has distinct advantages and challenges; the real point is to recognize that drumming is a journey rather than a final destination. Whether you resonate with the spontaneous energy of drum circles or the disciplined artistry of traditional drumming, what matters most is finding a path that aligns with your musical aspirations and personal growth.

Having studied traditional Haitian, Afro Cuban, West African and many other rhythms myself, I can vouch for the time and effort required to develop an ear for these intricate styles. But once you achieve that understanding, it can revolutionize how you perceive and interact with music. If you are transitioning from a drum circle environment, your newfound appreciation for traditional techniques may profoundly enrich your understanding of rhythm and composition.

Ultimately, let’s refrain from setting drum circles against traditional drumming. Instead, we should celebrate the diverse array of drumming styles and approaches, recognizing that there is a place for each in our vibrant community. Every rhythm tells a story, and every style offers a unique lens through which we can explore the universal language of music.