Back in the 70s, drummers with a vast knowledge of world rhythms from different genres were pretty rare. Of course there were some, but not like today.

Very few had the chance to travel to places like Africa to study with masters or experience the rhythms of Cuba. Milt Holland legendary percussionist did. Nowadays, that couldn’t be more different—anyone can book a flight and find programs ready to teach them these styles. And it’s great! I have gone on countless trips to study.

It wasn’t that drummers back then weren’t intelligent; it was just that access to knowledge was incredibly limited, especially for those not deeply involved in a specific drumming culture. It was not out there and easy to find. You had to know someone who knew someone. I know it’s hard to believe, but this is how it was.

The recordings of folkloric music were almost non-existent, with only a few options like the Folkways Records label and a select few Cuban albums available.

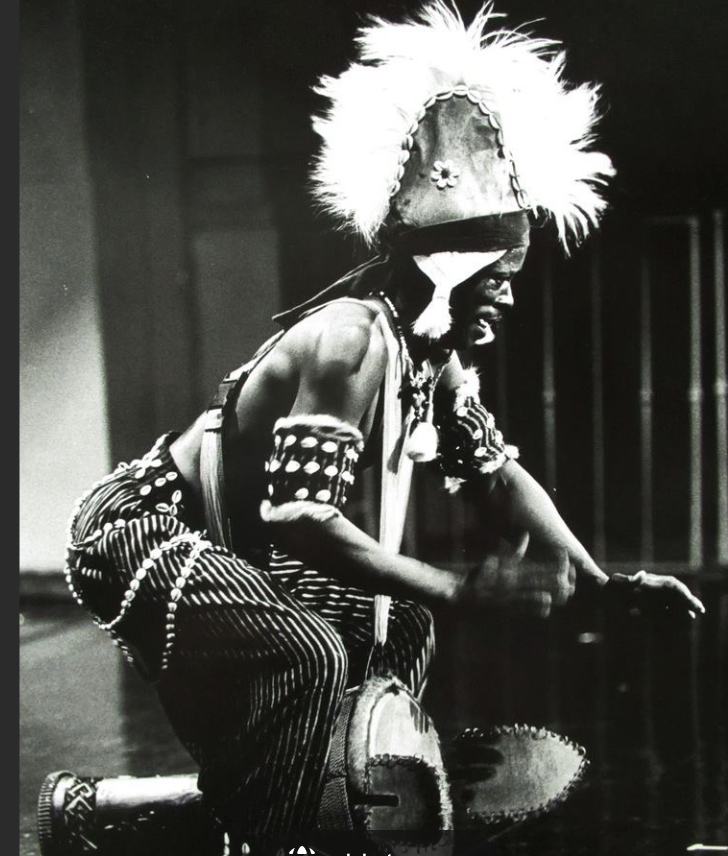

Finding Adama Drame in the late 70s was like striking gold for me. His father is reputed to be the first to record djembe music. I also discovered Africa Djole around that time, along with Gina Martinez and the Conjunto Folklorico Nacional from Cuba. These artists really opened up new worlds of rhythm to me.

Whenever I would go into an obscure record store and find something it was incredibly exciting. Yes, there used to be stores where you went and bought records!

Even within their own cultures, drummers often had a solid grasp of their own traditions but found it hard to gain insights into others. And at the time it was not needed. It was not about how much you knew or how many different things you knew.

This was largely due to the times and circumstances—who was traveling where, who was meeting who, and of course, the absence of social media.

Now, zoom forward to today, and we’re surrounded by an abundance of information. Spiritual seekers, yoga practitioners, and meditation enthusiasts have access to countless resources like online courses, books, magazines, seminars, and workshops. Concepts like “karma” and “bad karma,” once limited to spiritual talks, are now part of mainstream discussions. We now have more information than we know what to do with.

However, this flood of information can be both a blessing and a curse. We’re bombarded with knowledge but often struggle to make the most of it. We might catch a glimpse of a phrase or concept that could help us, but sorting through everything to find what’s truly valuable can be challenging.

The drumming community faced a similar situation back in the 70s; there was minimal interest or opportunities for sharing knowledge among drummers. Recorded drum music was scarce, and it wasn’t until the early 80s that seminars and classes started to appear.

Drummers from my era—the late 70s and early 80s—had a certain confidence rooted in the limited knowledge we had. You played what you knew and got good at it.

Whether we were right or wrong, we played with conviction and intention, totally immersed in the information we had. With fewer distractions at the time, our focus was all about mastering the grooves and playing as strongly as we could, connecting deeply with each other through the music.

Interestingly, that lack of information often led to a beautiful exploration of rhythm and technique.

There was something special about digging deep into a few key ideas, allowing us to interpret and express them uniquely every time we played. It turned out to be a blessing in disguise; with fewer sources around, we could explore more deeply.

Now, in contrast, beginner and intermediate drummers have access to a staggering amount of information right from their smartphones, including excellent apps like Djembe Fola.

Many might memorize countless patterns, but the burning question remains: do they truly understand and feel those rhythms the same way drummers of the past did? Unfortunately, many don’t.

Despite being surrounded by so much information, a lot of drummers still feel unprepared because they haven’t genuinely concentrated on or fully learned anything.

Recently, I spoke with a student who felt overwhelmed by the sheer volume of options. He asked me, “What should I focus on? There’s just so much to learn!” I suggested that if he worked on mastering the basic djembe parts for each rhythm family, that would empower him to play a wide variety of rhythms without needing to know all the intricate details.

Plus, mastering the 12/8 bell pattern would help him feel the pulse in any rhythm. It all boils down to getting the fundamentals down.

To make my point clearer, I shared a story from my time studying Gung Fu in San Francisco. My teacher, a highly skilled fighter, returned from China with a black eye.

We were all amazed and asked what had happened. He explained that he had a sparring session with a friend who was a boxer. No matter what move he made, the boxer had a perfectly timed left jab to counter it.

The boxer’s mastery of that one move was so complete that my teacher couldn’t keep up at all. This story illustrates how vital it is to really focus on mastering one thing before trying to do it all.

In my journey, there are still rhythms and solo patterns I’ve been working on for years, and I feel they’re always just out of reach.

But that’s the beauty of drumming and the ongoing challenge—it’s a lifelong quest for refinement. We only have a few basic sounds to produce: slap, tone, bass—and mastering the dynamics and variations within those sounds can take a lifetime.

I have a vivid memory from my time in Japan. A friend of mine was a sushi chef, and he took me to a tempura bar where the dining experience was special.

The chef would serve each guest one piece of tempura at a time, based on his own choice. After the last guest left, my friend had a long conversation with the other chef in Japanese, which I couldn’t understand.

Later, I asked him what they talked about, and he chuckled, saying, “He was telling me about his chopstick technique for dipping tempura!” It struck me how even the simplest techniques could spark such rich discussions about mastery.

So, whether in drumming or in life, focusing on mastering the basics can lead to a profound understanding of the art form. Instead of getting lost in the ocean of information available today, let’s concentrate on what truly matters and strive for mastery in our practice.